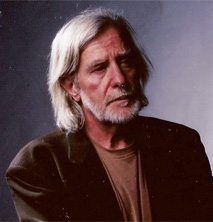

Interview with Producer and Director George King

Int: Why did you make this film?

GK: In a modest way, I learned how to make films in hopes of changing the world a bit — to present people with information that would challenge their thinking, attitudes, and perspectives. I believe that communication is the antidote to conflict — where there is communication — conflict is reduced. The prejudices that continue to divide us are perhaps the most significant impediment to progress. The legacies of American history and the culture that followed make race and related behavior one of our society's most divisive elements. Without communication across racial lines, and without knowledge about the diversity of America's histories, traditions, and experiences, nothing will change.

I made this film because I recognized the significance of the African-American

Great Migrations and the impact that they have had on contemporary history

and culture.

Many Americans are not aware of this history. Outside of academic circles, there is precious little information available about the migrations — particularly the second wave during the 1940's, '50's and 60's. And finally, there were no films or television programs on the subject.

I became aware of the migrations while working on another film (You Can't Judge a Book by Looking at the Cover, 1987) about the working methods of a friend, theater artist, John O'Neal (Junebug Productions, New Orleans). O'Neal, who at the time was the director of the Free Southern Theater, (the one-time cultural arm of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, SNCC), was working on a cycle of plays built around a mythical embodiment of black folk wisdom, Junebug Jabbo Jones. One of the plays was about the Great Migrations and the rapid transition of African-American's roots to a primarily urban ethnic group.

Int: I notice that you usually write your own films

why did you decide to work with a writer on this project?

GK: I am Anglo-Irish, I grew up in England, came to the U.S. in 1978. I was very sensitive to a couple of things; one I didn't grow up learning about American history and secondly I am aware of the history of whites interpreting non-white history and culture. It's complex. Clearly there are many remarkable works of scholarship, many referenced in our website resource guide, where white Americans have written about black American history and culture.

In addition, I find social class to be an important and often ignored element. Whereas I recognize that race is an important component in consciousness, it is not the only component. Middle class black filmmakers may be as distanced from the experience of working class subjects as their white counterparts. Ultimately I think that there should be many films made about the migrations from many different perspectives collectively reflecting the richness and diversity of experience and reality.

At the time, there were no films out on this subject and I didn't see anybody beating

the doors down to make a film about the migrations. And nobody's made a film

about it since (except for a BBC/Discovery Channel production). But I did feel the

need to make sure that we were telling a story that would resonate for an African-American audience and thought it important to work with somebody who came

out of that background.

Writer Lou Potter is African-American, he grew up in Philadelphia, the son of a prominent educator, he is very knowledgeable on American History and a successful writer of many films, particularly in collaboration with New York director St. Clair Bourne. Ironically, when I first met Lou he was working on a film about Ireland, so I figured he was the perfect foil to an Irishman making a film about an aspect of African-American history.

Int: Talk a little about

the process of making this film...

GK: I wanted to try and tell the story of

the Great Migrations through the

experiences of one family who moved

from the Mississippi Delta to Chicago, in

many ways the "classic" migration

experiences. I thought this would keep the audience's interest and enable them to

navigate through the many facets of this complex story.

As I pre-interviewed over a hundred

people during the research phase, I

realized that there is no "typical" family

that will represent all the shades of

experience that we wanted to reflect in this film. But in our research and thanks to

Chicago historian, Marvin Goodwin, we discovered the remarkable phenomenon

of migration clubs in Chicago. At the time

(1989 or so) there were a number of social

clubs made up of former migrants-usually based around the member's hometown.

So there was a Greenwood Club, a Clarksdale Club, and others, and we settled on the Greenville Travel Club, with members

who grew up in Greenville on the banks

of the Mississippi in the heart of the Delta.

The film intercuts a series of

"home movies" of the Greenville Travel

Club returning to their home town for a reunion.

Int: There's another element that re-appears throughout the film-the simulated newsreels.

GK: Yes, I wanted to call them "fake" but everybody told me that was a little blunt. We made the newsreels for two reasons. They grew out of the frustration of trying to find footage on urban African-American life, history and culture prior to the 60's. There's footage of the rural black experience, and some on Harlem, but precious little shot anywhere else. Of course the newsreel and film production companies were predominantly white-owned, and they had little interest in what was going on in black neighborhoods across town unless it involved violence or a disaster of some kind.

At the same time there was a certain amount of contextual information that we felt viewers needed to understand this epic story. I come from the school of filmmakers that prefers to avoid narration altogether, but ironically this film has three narrators: Vertamae Grosvenor, our orthodox narrator if you will, Viethel Wills from the Greenville Travel Club who narrates the home videos, and Bill Ratner who voices the newsreels. We created the newsreels as a device allowing us to give the viewer concise packages of information without resorting to more "orthodox" narration. It seemed entertaining and in the spirit of the time to use the buoyant newsreel style, precluded by the racial barriers of the time. We labeled them "simulated" to ensure no one believed they were real artifacts. For the record, there were a small number of newsreels produced by a black company for African-American viewers during the 1940s, but none of them focused on the issues we wanted to address in this film.

Contact the Filmmakers

To comment or ask question about Goin' to Chicago or this website, e-mail us at www.georgeking-assoc.com